Considering Place in Celebration of Native American Heritage Month

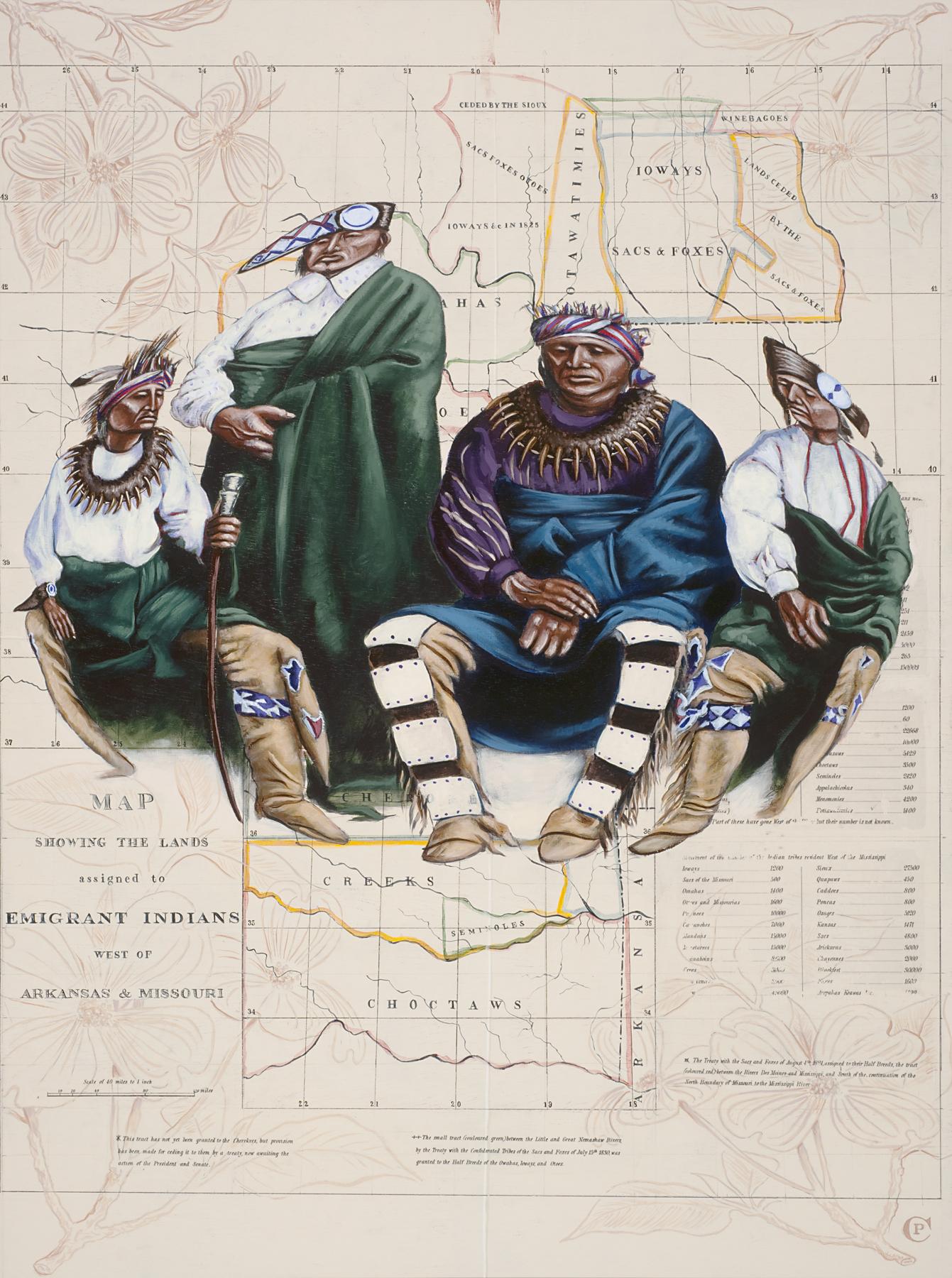

Chris Pappan, Displaced Peoples 2, 2011, Museum purchase: Peter T. Bohan Art Acquisition Fund, 2012.0010

Chris Pappan

Happy Native American Heritage Month! This November, and every month, we celebrate the joys, achievements, and resilience of Indigenous peoples through their art and culture. In honor of the tribes whose lands we now occupy, we are highlighting art considering the concept of place and artists affiliated with Kaw or Osage Nations, whose historic homelands are located in Eastern Kansas where KU and the Spencer Museum exist today.

In Displaced Peoples 2, Chris Pappan (Osage, Kaw, Cheyenne River Lakota Sioux) overlays Indigenous people on a map of present-day Kansas and Oklahoma, referencing the forced removal and relocation of tribes to Indian Territory. The distortion of the figures conveys how borders, while arbitrary lines on a map, can have immense impact on peoples’ lives, homes, and histories. It can also represent the distorted views many people have about Native Americans.

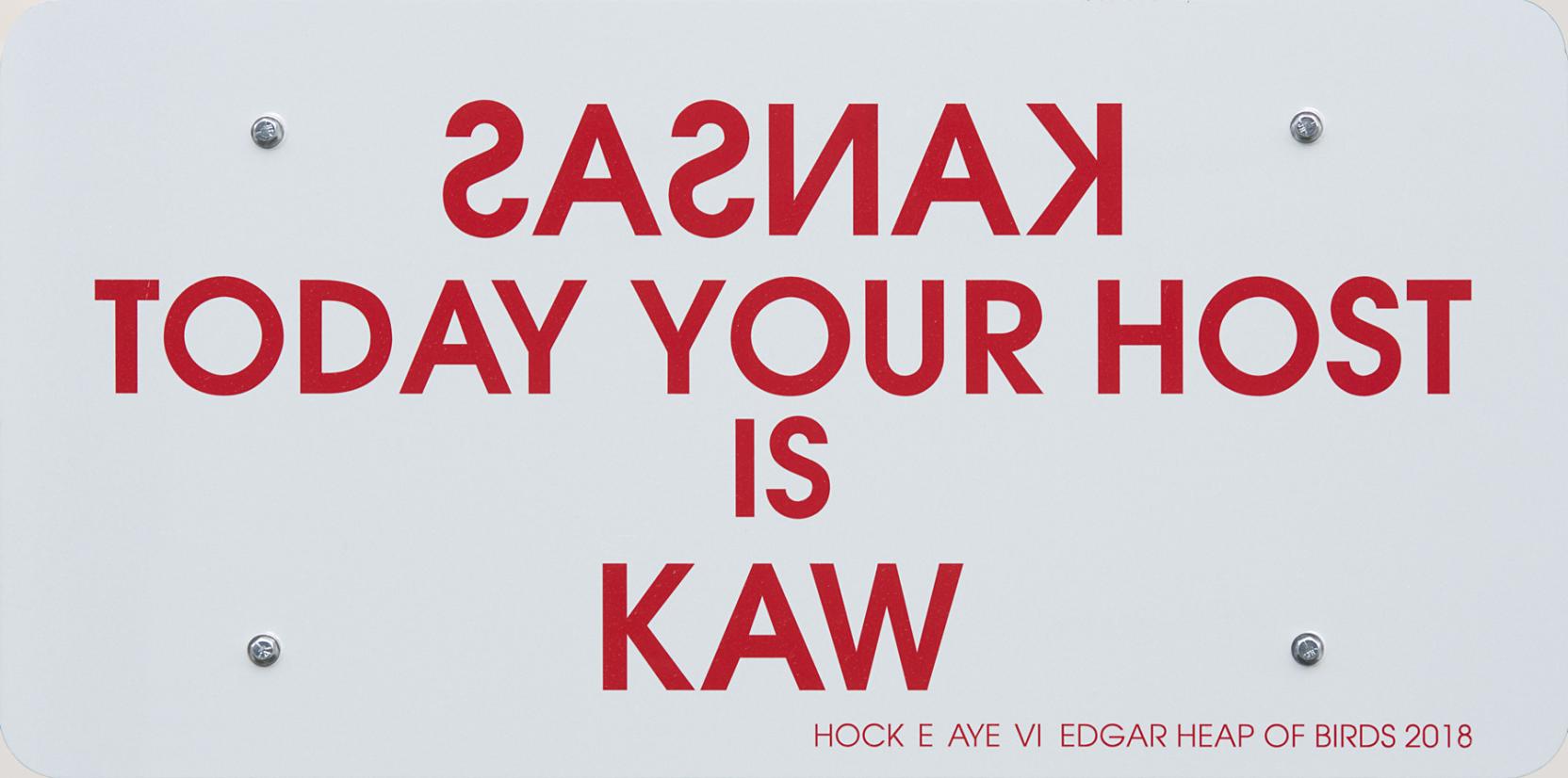

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds, Kaw, 2018, Museum purchase: Peter T. Bohan Art Acquisition Fund, 2018.0237

Edgar Heap of Birds

Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds (member of Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations), acknowledges and honors the Kaw, as well as the four federally recognized immigrant tribes with headquarters and reservation lands in Kansas today, with his Native Hosts series. While Kansas is written backwards, making it difficult to decipher at first glance, Kaw is written forwards. Heap of Birds hopes people will “wonder about the tribal identity that they are actually walking over.” Settlers would plant posts to claim and mark territory, often without consulting the Indigenous peoples inhabiting those lands. Countering this act of border-making, the Kaw sign is embedded into the ground, becoming an act of mark making and a reclamation of space. Installed near the entrance to the Spencer, Kaw and the other Native Hosts signs ask us all to consider how we conduct our lives as visitors and recognize whose land we occupy.

Listen to an interview with Edgar Heap of Birds about this series

Listen to an interview with Edgar Heap of Birds about this series

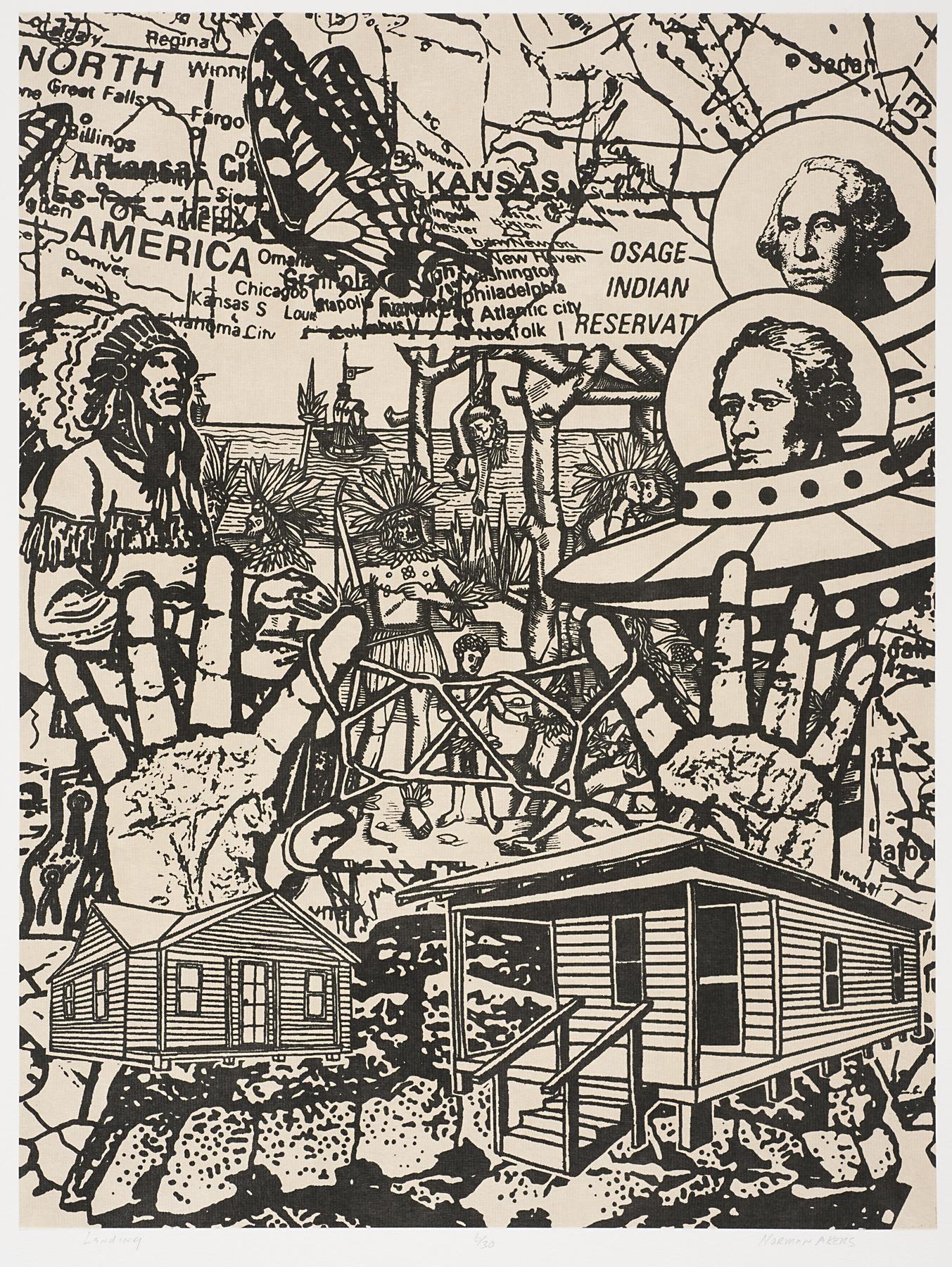

Norman Akers, Landing, 2019, Gift of the Print Society of Greater Kansas City, 2020.0014

Norman Akers

Norman Akers (Osage), a professor of visual art at KU, questions the concept of borders and immigration in Landing. The artist depicts George Washington and Alexander Hamilton in UFOs (unidentified flying objects) descending toward Indigenous lands. By presenting Founding Fathers of the United States as immigrants, Akers questions the narratives of illegal immigration and “alien” status. In addition, the two hands form a chain-link fence with string, reminding us that borders are human-made and are always in flux.

James Pepper Henry, Iⁿ’zhúje‘waxóbe & Stars, 2024, Courtesy of the artist, T2025.046

James Pepper Henry

James Pepper Henry (Kaw) took the Iⁿ’zhúje‘waxóbe & Stars photo in Allegawaho Memorial Heritage Park. Just as the Kaw people were displaced to present-day Oklahoma, Iⁿ’zhúje’waxóbe, or the Sacred Red Rock, was taken from its original location at the confluence of the Kaw River and Shunganunga Creek near Tecumseh, Kansas, to Robinson Park in Lawrence, Kansas. The Rock stood there for nearly 100 years as a trophy for the settlers who founded the city. The 28-ton red quartzite boulder was rematriated to land owned by the Kaw Nation through community efforts of the Sacred Red Rock Project. In celebration of the rematriation of Iⁿ’zhúje’waxóbe, Henry uses a longer exposure to capture the motion of the stars that form a halo above the Rock.

Ryan RedCorn, Portrait of Chantelle Keshaye Pahtayken & Shay Pahtayken, Plains Cree, 2019, Museum purchase: R. Charles and Mary Margaret Clevenger Art Acquisition Fund, 2019.0063.01

Ryan RedCorn

In the 10-foot-tall Portrait of Chantelle Keshaye Pahtayken & Shay Pahtayken, Plains Cree, KU alum Ryan RedCorn (Osage) undermines tropes Americans have about Indigenous people. Early black-and-white photographs of Native Americans documented what settlers believed to be a “vanishing” people. Through vibrant color, grand scale, and the portrayal of two successive generations, RedCorn counters and reclaims this narrative, which “forcibly places Indigenous people in the present with dignity and respect.”

Working in a variety of media, Indigenous artists continue to develop new ways of celebrating their heritage throughout generations. There are many more works on view and in our collection that attest to the cultural continuity and achievements of Indigenous peoples. Which ones can you discover on your next trip to the Spencer Museum of Art?

View another story

Beadwork and Horror: Jamie Okuma's Becoming